PFC James Loterbaugh - US Army

- pd-allen

- Dec 12, 2025

- 10 min read

November 5th, 2024, was an uncharacteristically warm and sunny day in the US Military Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands. I visited the cemetery to pay my respects in hopes that the 10,000 souls in the cemetery who had given their lives for freedom could somehow be called upon to preserve democracy once again. The cemetery has over 8,300 burials and a further 1,722 names inscribed on the tablets to the missing and I sat on a bench in the middle of the immaculate grounds urging the fallen to shine a light on this crucial day.

The gentle arcs of the gleaming white marble crosses shone in the sunlight but were not strong enough to overpower the tidal wave of disinformation.

The memorial tower houses the memorial chapel inscribed “In memory of the Valour and the Sacrifices which Hallow this soil”. Margraten was opened as a temporary cemetery in October 1944 soon after the liberation of the southern Netherlands and at one point, held nearly 20,000 graves. After the war the grieving families had the option to repatriate their loved ones so more than half of the fallen were returned to the United States.

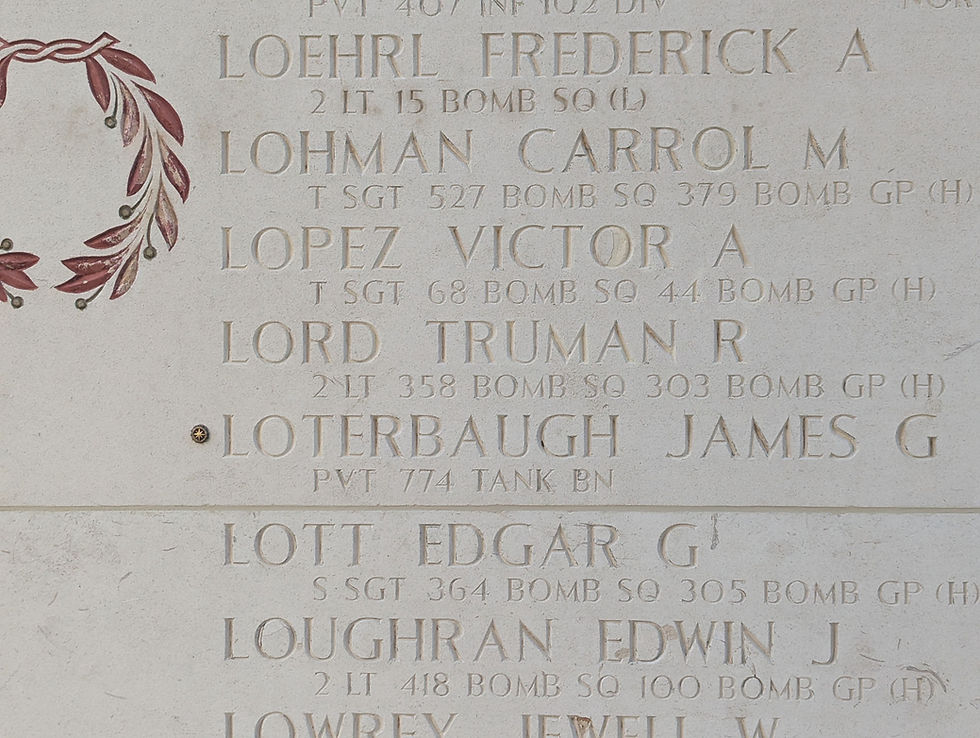

The entrance to the Margraten cemetery has a reflecting pool and the walls that line the path hold the names of the missing commemorated at the cemetery.

The Margraten cemetery has been in continuous use since 1944 but was rededicated in its current configuration in 1960. The cemetery was built in a former orchard, due to its excellent drainage and location near a major road.

Before the end of the war, the Americans had so many bodies that they called on the local Dutch people to help dig graves. Since the end of the war each grave and unknown listing has a Dutch family who cares for an individual soldier, placing flowers and memorials to show their sacrifice is not forgotten. The graves are often passed on from generation to generation as family heirlooms and there remains a waiting list to receive a grave to care for.

The cemetery is a little more well-treed today.

On my way out of the cemetery, I noticed a workman drilling a hole next to one of the names.

In US cemeteries, if the body of one of the missing is located, they place a rosette beside the name to indicate they once were lost but now are found. This is a different practice than in Commonwealth Memorials. At one point in the Commonwealth Memorials, the name of the missing man was removed from the memorial when the body was found, now they generally leave the names. At Vimy for example, no names have ever been removed from the memorial.

I had to hang around for a bit until the workman left but managed to get a shot of the name so I could look him up.

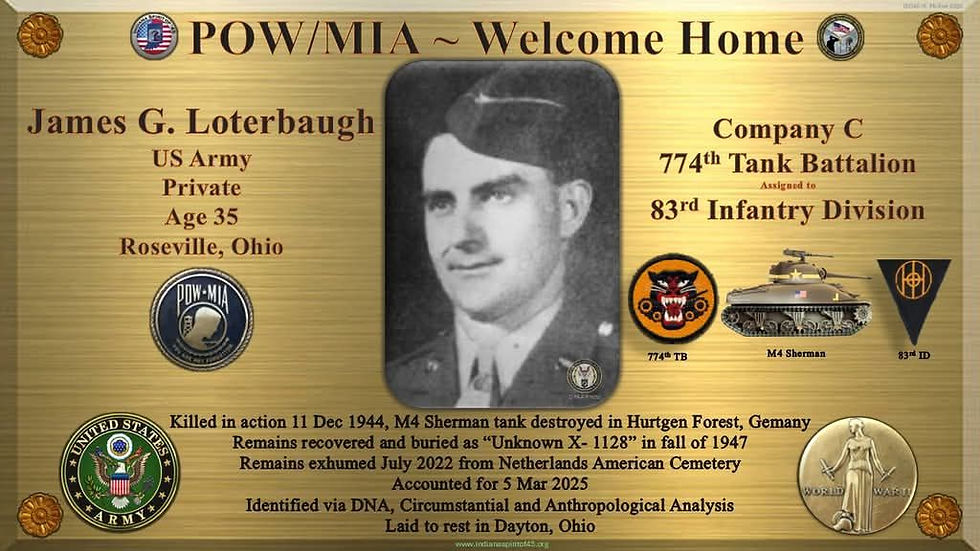

Private First Class James Loterbaugh of the 774th Tank Battalion from Ohio was my man. The rosette used to mark someone as having been found is visible next to Arthur Luce’s name. This was just a week before I returned to Ottawa, so I set my sister Dale onto an Ancestry hunt while I looked around for more details of James. I didn’t find anything, so nearly a year later when I was going to visit the cemetery again, I revisited his story.

James’ Story

In May 1944, James Loterbaugh was assigned to Company C, 774th Tank Battalion, as a crewmember on an M4 “Sherman” tank. On Dec. 11, his platoon became separated from the rest of the company during a battle with German forces near Strass, Germany, in the Hürtgen Forest. The enemy surrounded Strass and by mid-day the entire platoon, including Loterbaugh’s tank, was reported Missing in Action. The Germans never reported Loterbaugh as a prisoner of war and Army personnel who searched the battlefield after the fighting found no lead regarding his fate. The War Department issued a presumptive finding of death in December 1945.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel in Europe. They conducted several investigations in the Hürtgen area between 1946 and 1950. In the fall of 1947, investigators found unidentified remains in a destroyed tank near Strass. Officials designated them X-1128 Margraten (X-1128). Comparison and analysis were made, but at the time X-1128 could not be identified as Loterbaugh.

The US Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) started a program in 2010 to try to identify the Unknowns. Since Margraten has relatively few (106) unknown burials, an extensive documentary review was conducted and in 2022, 4 high probability of identification candidates were selected, and their graves were exhumed for DNA testing and further analysis. James was positively identified and his body repatriated to the military cemetery in Dayton, Ohio at the request of his family. At least 2 others from the same group have been identified and returned to the US.

According to the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) website, the headstone marked as Unknown is removed once the individual is identified and the grave may be reused for another unknown or left empty. This didn’t make sense to me as I had spent a fair bit of time walking the grounds and never noticed any missing headstones. So, I spoke with cemetery staff, and they looked up the marker location, and it is still assigned to X-1128.

James now has a rosette, showing he is found.

Dayton National Cemetery

James was buried in Dayton National Cemetery with Full Military Honors on 03 June 2025. Dayton is special to me, as I served as an exchange officer with the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base for 3 years and while we were there, our daughter Rachel was born.

Dayton National Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio, is the final resting place for approximately 60,000 U.S. military veterans and their families. This includes individuals who served in every major U.S. conflict, from the Revolutionary War through to the War on Terror.

The cemetery, established in 1867, spans 116.8 acres and is one of the few national cemeteries designated as a National Shrine. It remains open for new interments and is projected to have sufficient space until at least 2060. Notably, Dayton National Cemetery is one of only eight national cemeteries in the United States that contains the remains of veterans from every major U.S. conflict.

The massive extent of the cemetery.

James is buried in SECTION 42, SITE 2477.

The memorial certificate for James.

Memorial ID card generated for a found MIA.

PFC James Gilbert Loterbaugh - US Army Personal History

Early Years

James Gilbert Loterbaugh was born on March 25, 1909, Nelsonville, Athens County, Ohio, to George Gilbert Loterbaugh and Ida May Hills. James was their third child out of 9. At the time of James birth, George was a Coal Miner and Ida May was a homemaker. The family rented their home. Ten years later, George was still a Coal Miner, and the family had four more children for a total of 7.

In Ohio’s early years, clay deposits were discovered along a number of riverbanks and small-scale stoneware potteries sprang up to meet the utilitarian demands of a growing population. Many in the Loterbaugh family worked in that industry.

In 1930, George and Ida owned heir own home and George, now aged 52, left the coal mines and was working as a packer in the pottery industry. James and brother Andrew were also working in the Pottery industry as laborers. The Loterbaugh’s now had 8 children.

In October 1938, James married Esther Alpha Shipley. James had completed 8th grade in elementary school. He now ran the Kiln Drawer for Robinson Ransbotton Pottery Company in Roseville, Ohio. The couple lived in Roseville, Muskingum County, in Ohio. Esther had previously been married to James Richard Mauller, James former next-door neighbour. Esther and Richard divorced on 22 June 1938, and Esther cited the reason for divorce as cruelty.

James Loterbaugh and Esther had a son, James Lewis who was born on February 1, 1940.

Military Service

James was enlisted into the US Army on 13 January 1944 at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana just outside Indianapolis. This was an intake centre, James was subsequent sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky for basic training. At Fort Knox, members went through a combined basic and armored training course that lasted 17 weeks so he would have graduated in May 1944 and was assigned to C Company of the 774th Tank Battalion.

James was assigned the Military Occupational Specialty 795 – Tank Crewman. The Tank Crews were trained to perform all basic armoured crew functions including Driving, Weapons and Gunnery, Communications, Maintenance and Tactical Deployment.

774th Tank Battalion

The 774th Tank Battalion trained initially at Camp Blanding, Florida, after activation in December 1941. They then completed desert training in California with the 7th Armored Division by September 1943. The desert training had been set up to support the US troops heading to Africa.

M3 Tank

The Battalion trained first on M3 Lee then M4 Sherman Tanks. Afterward, they organized at Fort Benning, Georgia, moved to Camp Rucker, Alabama, and conducted further training in the Tennessee Maneuver Area in early 1944. They received notification of deployment and returned to Camp Campbell, Kentucky. James would have joined the unit there. Just before overseas deployment, they prepared for a month of training, concentrating on indirect firing (i.e. using the Tank Gun as an artillery piece).

M4 Sherman Tank

On 25 June the Battalion arrived at Camp Shanks, New York and on 1 July boarded the troopship Dominion Monarch, to the strains of music by a Women’s Army Corps (WAC) band. The Battalion arrived in Scotland on 12 July, after being trailed the last few miles by enemy U-boats, and on the 15th arrived in Barnstaple, England, the new home station of the 774th.

The Dominion Monarch was primarily a refrigerated cargo ship and was the largest ship ever built with all first-class accommodations.

On 24 August the Battalion sailed from Portland Bay on Landing Ship Tanks (LST’s), disembarking at Utah beach on the 25th. The first mission assigned the 774th was to protect General Patton’s right flank in his push through France.

By October, the 774th Battalion was in Luxembourg supporting Infantry in cleaning out towns along the Moselle River and were employed in the secondary mission sending over 11,000 rounds of indirect fire into German soil across the river. A line of Canadian Sherman Tanks conducting indirect fire in Italy.

In early December, the Battalion moved into the bloody Hurtgen Forest front in Germany to support the 83rd Infantry Division in driving the enemy from the area southwest of Duren to the Roer river. The US had unsuccessfully been trying to clear the Hurtgen Forest since September and had used up several Divisions. The 83rd Division was the latest group to be thrown into the battle.

December 8th marked the initial phases of the operation. The difficulties of this attack were apparent from its inception. The enemy had made extensive and strategic employment of mines throughout the area held high terrain affording his use of direct fire weapons to canalize approaches to the Roer. On 10 December, Companies B and C attacked the key towns of Gey and Strass respectively, and met fierce opposition from enemy tanks, high velocity antitank guns and machine gun fire as well as undergoing mortar and artillery fire. Elements of the two companies and infantry succeeded in reaching the towns but were almost entirely cut during the three succeeding days. Limited quantities of supplies and ammunition were brought to them, under cover of darkness by tanks of A and D companies, over routes that had been re-mined and that were under constant observed artillery and mortar fire. 774th Tank Battalion wading through the mud.

Private First Class James Gilbert Loterbaugh was assigned to Company C, 774th Tank Battalion, as a crewmember on an M4 “Sherman” tank. On Dec. 11, number one platoon became separated from the rest of the company during a battle with German forces near Strass, Germany, in the Hürtgen Forest. The enemy surrounded Strass and by mid-day the entire platoon, including Loterbaugh’s tank, was reported Missing in Action. The Germans never reported Loterbaugh as a prisoner of war and Army personnel who searched the battlefield after the fighting found no lead regarding his fate. He was officially declared dead in December 1945.

The Hurtgen forest was located at the Siegfried Line, the major German defensive line between Aachen and Monschau. The Battle of Hurtgen Forest raged from September to December 1944 and was one of the costliest battles fought by the US Army in Europe. The Dense woods eliminated the US air superiority and made armour nearly useless. As part of the main German defensive line there were extensive mine fields, barbed wire, camouflaged pillboxes and artillery that inflicted heavy losses. It was a very cold and wet fall so what few roads existed turned into a sea of mud. The terrain was very hilly and when shells hit the trees they shattered and rained deadly branches down on the troops.

Bunkers on the Siegfried Line.

Dragon’s Teeth Anti-Tank Defences on the Siegfried Line.

US Army commanders insisted on clearing the forest despite a clear path through the Monschau corridor as they were concerned about attacks from the flank. The following map shows the very limited progress over a 3-month period.

The US Army threw Division after Division in an attempt to make a breakthrough. The 83rd Division which included the 774th Tank Battalion, was the last Division to enter the fray. The US Army suffered 55,000 casualties during the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest, with 33,000 combat casualties and an additional 22,000 noncombat (trench foot, frostbite, exhaustion). The 83rd Division suffered over 2,700 casualties for the period 4-16 December 1944.

No sooner had the Americans finally succeeded, than the Germans launched their major counter-offensive, known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The details of the 774th Tank Battalion travels from landing at Utah Beach on 25 August until the end of the Battle of the Hurtgen forest are shown on this map.

An interactive map is also available.

Final Thoughts

Fortunate timing led me to the discovery of James Loterbaugh. I really enjoy pursuing collateral stories, the ones that pop up while you are looking at something else. Although the Hurtgen Forest is about an hour from Rachel’s house in Maastricht, I have been resisting opening another front for battles that didn’t involve Canadians. The Battles of the Hurtgen Forest may force me to expand my horizons as it is another fascinating story. Of course, this opens up the Battle of the Bulge and the Germans going through the Ardennes in the First and Second World Wars, so many more battlefields to walk.

The Americans have a different approach to burials than the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). Firstly, the Americans permit the reparation of the bodies at the direction of the families and secondly, they have an active program to try to identify Unknown Soldiers. The CWGC will entertain any analysis to try to identify Unknown Soldiers but have a very high standard of proof so not many Unknown Soldiers become named. They also do not permit exhuming the body from a cemetery for DNA analysis. If bodies are found outside of a cemetery, full analysis is carried out by the soldier’s country. Canada currently has 42 soldiers it is trying to identify.

I do like how coincidences happen and lead you to a whole new line of research.

Did you visit the cemetery in Ohio when you were living there or were you too busy with other stuff. It looks beautiful there. I am glad to hear what happened to James. I should see if I can find out anything about his son. Not being a history scholar in high school, I do remember the Seigfried line. It looks even more treacherous with the photos and story about all the attacks. Thanks again.

Thanks Kurt. I am fascinated by what you can dig up on these guys.

Good storey. Amazing how much You are able to find after 80 or so years. Great work, thanks.

Kurt.